Sources of Trust in Uncertain Times

Caroline Loewen

Trust is foundational for maintaining the legitimacy and sustainability of public institutions, including museums and heritage sites. And at a time when confidence in public institutions appears to be increasingly tenuous, museums continue to hold the trust of Canadians. Data collected over the last several decades in Canada affirms the steady trust that the public has in museums.

In 2006, a collection of academic researchers, universities and community partners launched a project called Canadians and Their Pasts to explore how ordinary Canadians engage with the past in their everyday lives. The results of a 2007-2008 survey conducted by York University’s Institute for Social Research as part of the project provide insight into, among other things, the trustworthiness of sources of information about the past. The researchers found that about two-thirds of respondents thought museums were very trustworthy. For context, just 39% agreed books were very trustworthy, 32% for family stories and 29% for teachers. Even people who do not visit museums trusted them at a similar rate as museum-goers. This research also found that the level of trust did not substantively change when selecting for socio-demographic subgroups of the population, with one notable exception. Fewer than half (46%) of Indigenous people surveyed rated museums as a “very trustworthy” source of information, citing that Indigenous people put more trust in family stories.

Similar research conducted by the Department of Canadian Heritage in 2016 showed the public trust in museums remained high, with 96% of Canadians believing museums were trusted sources of information about history. Levels of trust increased as education increased. This research also showed that, while Indigenous respondents indicated overall that they trust museums (94%), they were more likely than non-Indigenous respondents to rate the level of trustworthiness as “somewhat” rather than “strongly.”Events over the past few years — the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the COVID-19 global pandemic, increasing globalization and growing inequality, the urgency of the climate crisis, and more — have reshaped our views of the world. Amid this uncertainty and upheaval, cultural institutions are increasingly wondering what their role is, and how they can remain sustainable and relevant to their communities. At the core of these questions is the issue of trust. Are museums still seen as trustworthy?

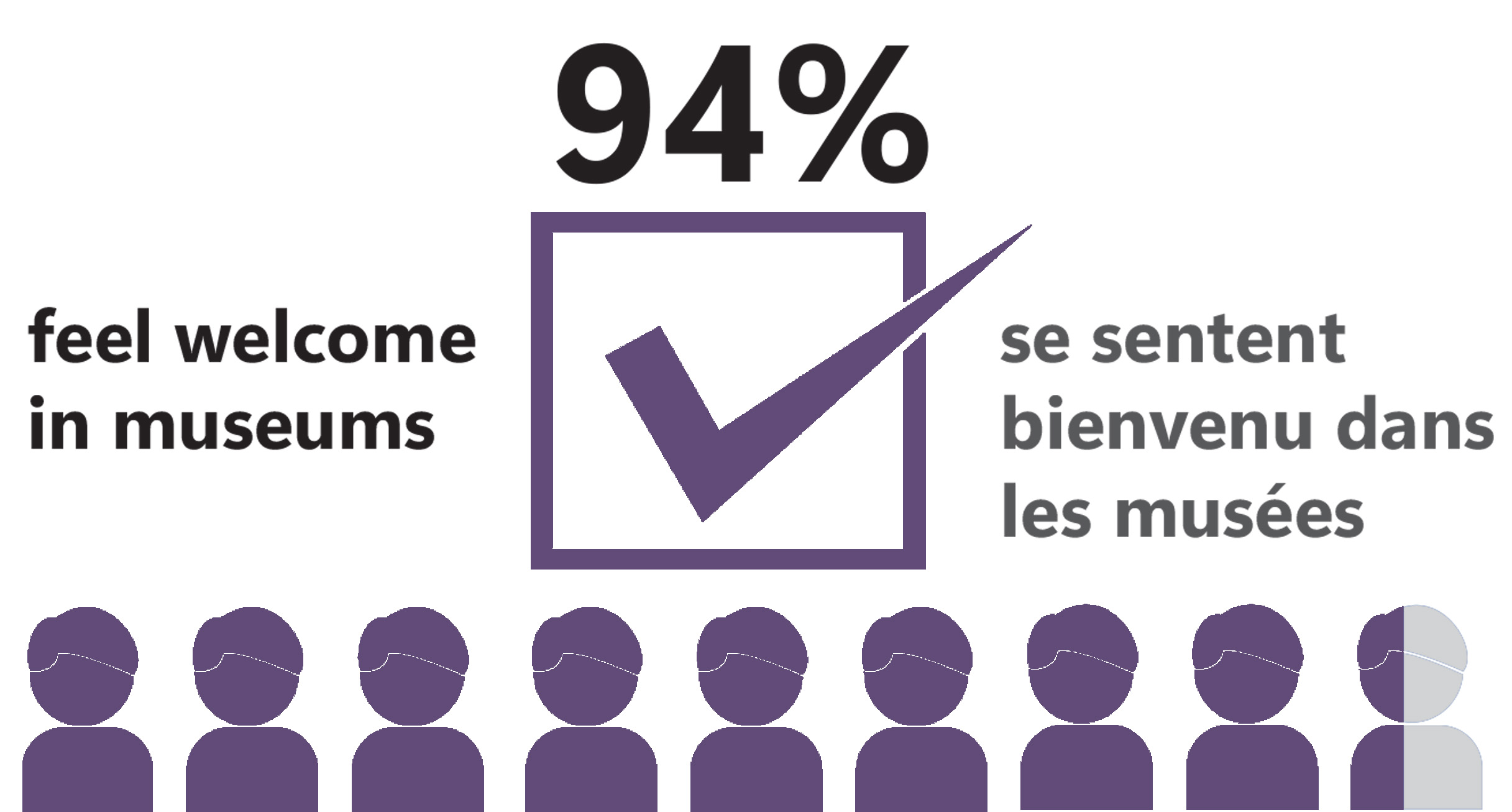

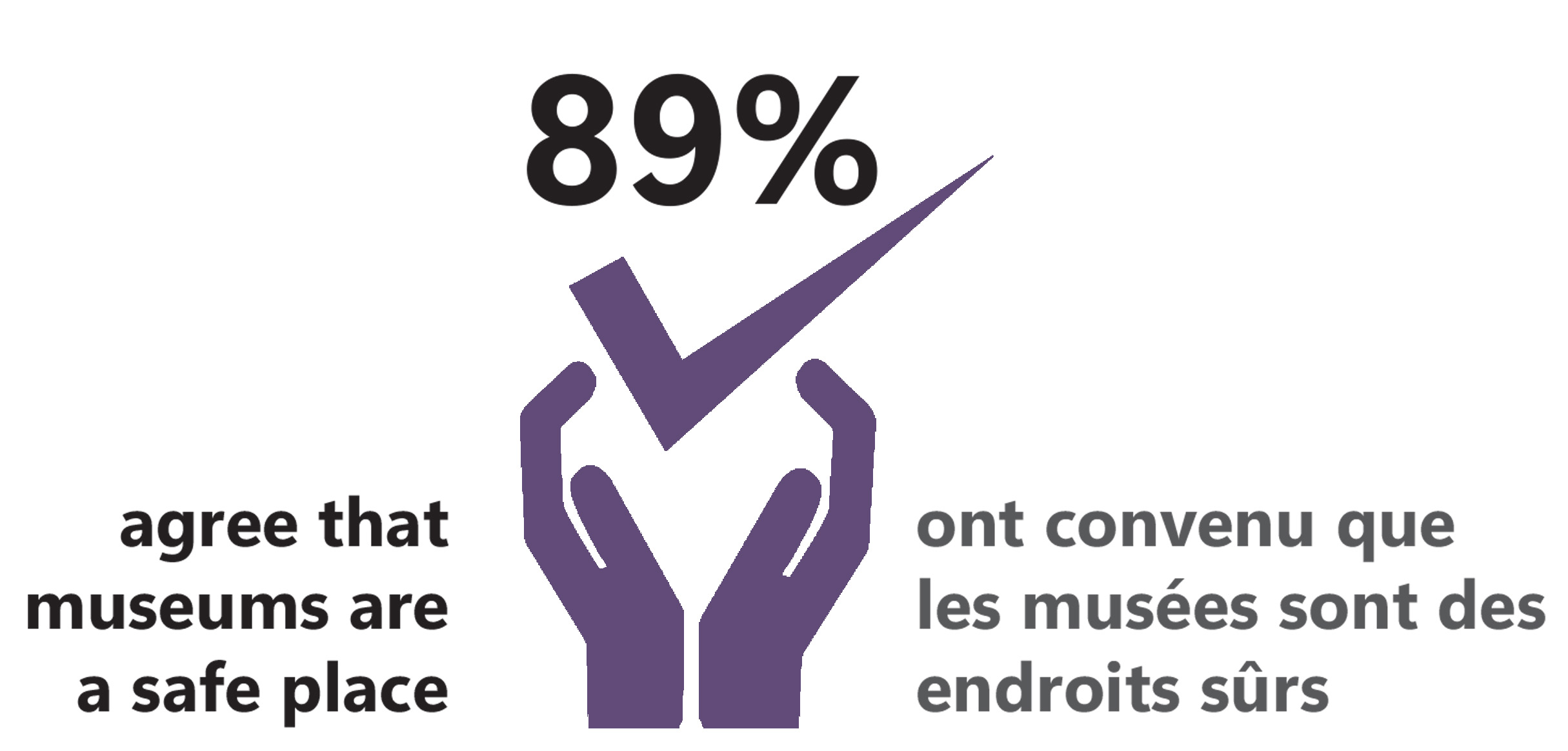

Reconsidering Museums

In 2020, the Alberta Museums Association in partnership with provincial and territorial museums associations and the CMA launched a three-year national project called Reconsidering Museums. The first phase of the project, Museums for Me, asked Canadians, what do museums mean to you? Responses to this question were collected through an engagement campaign consisting of an online survey, public opinion polling and virtual dialogue sessions, some of which were revealed in the Fall 2021 issue of Muse The data collected through Museums for Me affirmed insights from previous studies. People continue to feel comfortable in museums: 94% of survey respondents reported feeling welcome in museums and 89% agreed that museums are a safe space. Most importantly, the public continues to trust museums and considers them a credible source of information.

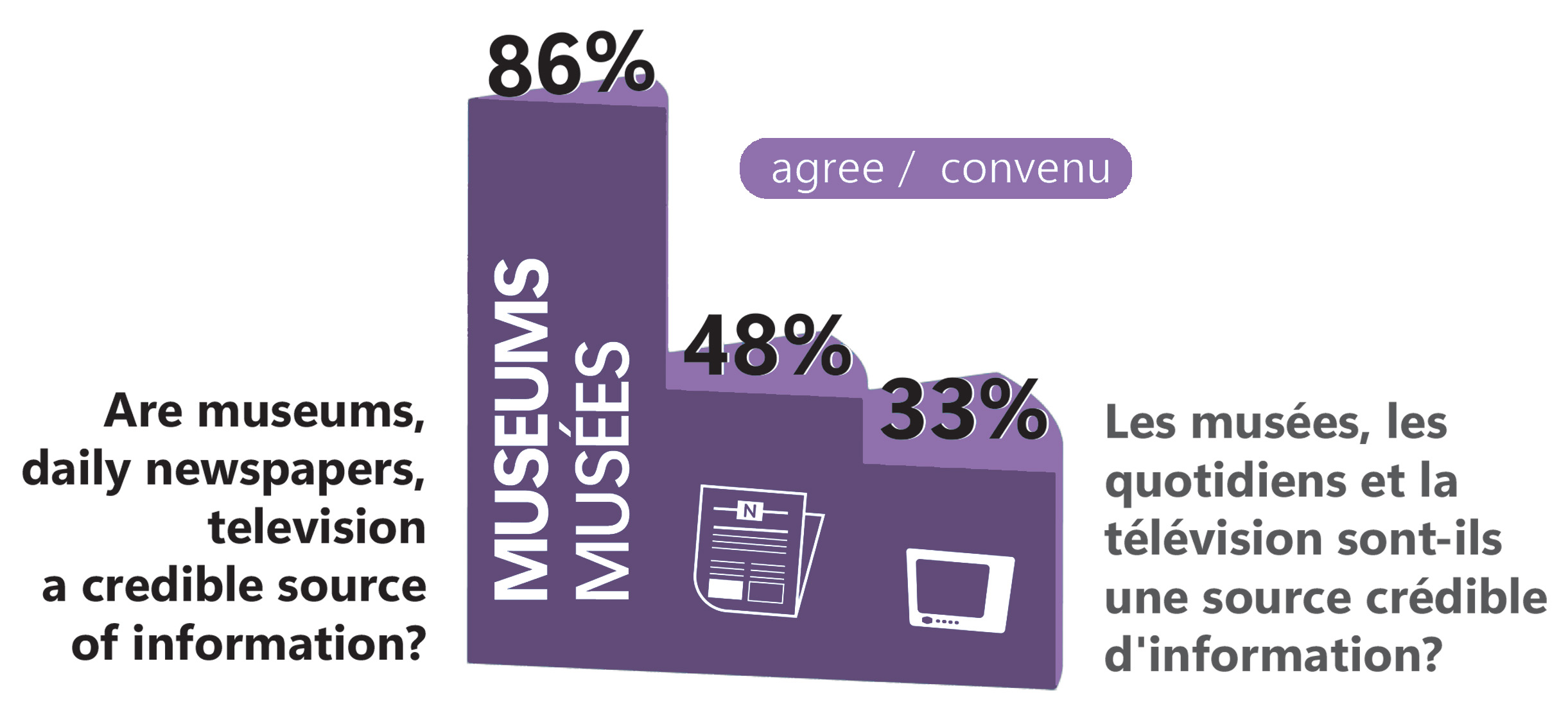

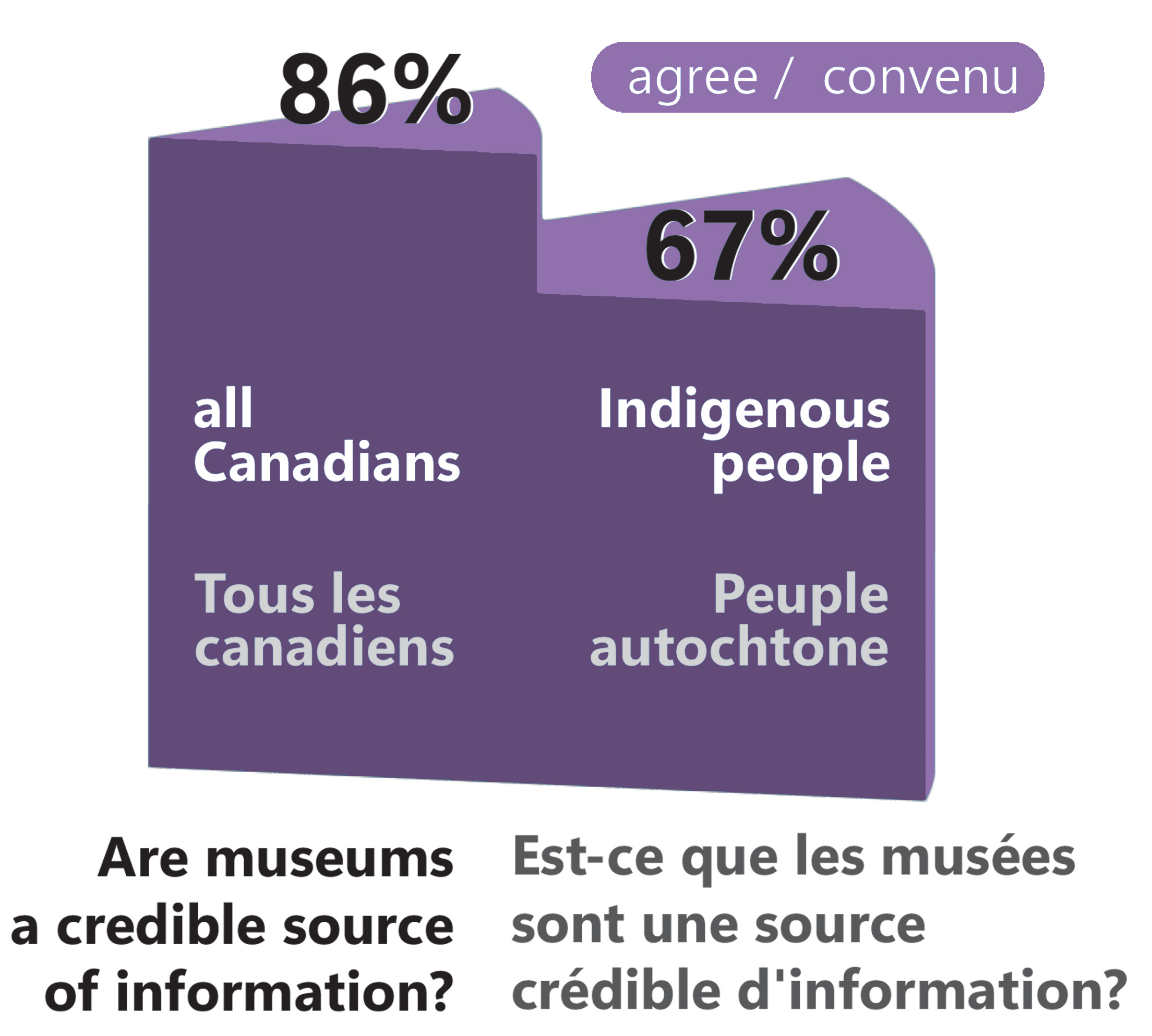

The public opinion polling revealed that 80% of people perceive museums as a credible source of information, surpassing daily newspapers (48%) and television (33%). As seen in the earlier surveys, the data showed that Indigenous people are slightly less likely to trust museums: only 67% agreed that museums are a highly credible source of information.

It is not just museum-goers who hold these views: research consistently shows that even people who do not visit museums consider them trustworthy. A key takeaway from a landmark 1974 study, The Museum and the Canadian Public, was “a great number of respondents strongly support the concept of the museum while for the most part avoiding the reality.” Canadians value and trust museums, regardless of how often they actually experience them.

So why do people continue to trust museums? It could be that the public perception of museums as safe, welcoming and impartial spaces makes museums inherently trustworthy. Researchers for Canadians and Their Pasts posit that “trust in museums is akin to faith. It is both earned and bestowed on museums. Bestowed because there is a belief that artifacts speak for themselves. Earned because there is a belief that the system has dedicated researchers and there are checks and balances on what researchers say about the artifacts.” There appears to be a base level of trust in museums, founded partially on the presence of objects and the assumption of expert knowledge.

A 2021 article for the American Alliance of Museums, called “What Does it Mean to be Trustworthy,” suggested “that trust was based on an assumption by the public that museums offer unmediated experiences and do not interpose ideas between the public and the objects.” The public’s trust in museums, then, would seem to be based on false assumptions, even at odds with how museum workers perceive the work that they do. After all, most museum workers would agree that museums are not neutral and do not offer unmediated experiences.

By focusing on how to continually earn the trust of their communities, museums can demonstrate that they are worthy of that trust. As one respondent to Museums for Me put it, “when done right, museums can be one of the few places that still hold community trust.” As soon as museums start to take that trust for granted, they are at risk of losing it.

Let’s further explore two reasons why museums are considered trusted: their collections and their multivocality.

Collections

Canadians look to museums to teach them about the world, the objects and the histories of their communities. Respondents to Museums for Me cited preservation and learning as the key functions of museums. These two functions are connected. Museums preserve both tangible and intangible heritage, so that visitors can learn about our shared past. As one respondent put it, “museums preserve common inheritances. They keep objects and archives as historical evidence.” Similarly, another respondent said that “museums taught me about new ways to communicate. They taught me the value of objects as messages from other times or places.”

The public sees museums as places where they can have a physical and intellectual experience with museum collections, and those collections can teach them about their histories and the natural world. In the minds of the Canadian public, artifacts offer an objective look at the past or nature. But museum workers know that collections are not objective representations of either. Artifacts, specimens and their histories are also not neutral. How they are selected and collected, catalogued, stored, researched and made accessible impacts how the collection is perceived and interpreted. Source communities, including many Indigenous communities, know this all too well. If museums are in part trustworthy because of their collections, then they need to be transparent about the people, places and communities they collect from, how they collect, how researchers name and categorize objects, how accessible their collections are and how they display their collections.

Multivocality

According to our research, museums have the potential to speak with many voices. Respondents indicated that “museums are for perspective, to widen our worldview and build historical consciousness.” Museums “take me beyond my own experience” and “are a place for dialogue and exploration on issues.” The perception that museums are places to dialogue, to ask questions and to seek out differing views contributes to the trustworthiness of the institution. The more voices included, whether those voices belong to museum workers or community members, the fuller and, presumably, more accurate the picture. At the same time, Canadians want museums to be places for trusted information on issues that matter to them, like technological advancements, diversity and inclusion, and reconciliation.There is still work to be done to enhance the multivocality of museums. More than 50% of Museums for Me respondents still think that museums need to better represent all Canadians. Museums are seen to be trustworthy when they present all sides of a story. To maintain that trustworthiness, museums need to reimagine their relationship with the “truth” and their own authority. Can museums create space for uncertainty, ambiguity, multiple narratives and differing perspectives? If they want to remain relevant and trusted, they might need to.

Conclusion

Museums have always enjoyed the trust of the public, both earned and bestowed. Our publics are increasingly educated, engaged and demanding, and the pressure on museums to be deserving of the confidence placed in them is increasing. Rather than resting in the knowledge of what they have, museums should be continually working to remain worthy of the public’s trust. M

Caroline Loewen is the Project Lead for Reconsidering Museums. She is a Calgary-based curator, writer and museum worker. She is passionate about helping museums become more inclusive, accessible and engaging spaces, where a diversity of voices and perspectives are included and valued.

She would like to acknowledge Dr. Victoria Dickenson, who provided numerous notes, references and editorial support for this article.

For more information on the Reconsidering Museums project and Museums and Me initiative, visit https://www.museumsforme.ca